ORGANIZING AND WRITING

ASHRAE STANDARDS AND GUIDELINES

PLANNING | WRITING | PROCESS | REVIEW

Introduction

This is a brief guide for organizing and writing ASHRAE standards and guidelines. It’s intended to be read in full by ASHRAE Project Committee chairs and member-authors.

Disclaimer: Some examples in this guide were created with the assistance of Google Generative AI. ASHRAE makes every effort to honor copyright. Please contact the Editor of Standards with questions, comments, or concerns

Principle of Design

ASHRAE publications are designed to meet the needs of users. Usability is the most important feature of every standard and guideline:

- A document that’s poorly organized or written is difficult to use.

- A document that’s difficult to use is difficult to implement.

- A document that’s difficult to implement will have lower impact: fewer sales, fewer applications, and fewer references in research, standards, and code.

When planning, writing, and reviewing your document, ensure that every choice positively impacts usability.

Contents

This information, when applied, will produce more effective and impactful standards and guidelines:

Return to Top

PLANNING

ORGANIZATION AND STRUCTURE | COORDINATION | TIMELINES

Organization and Structure

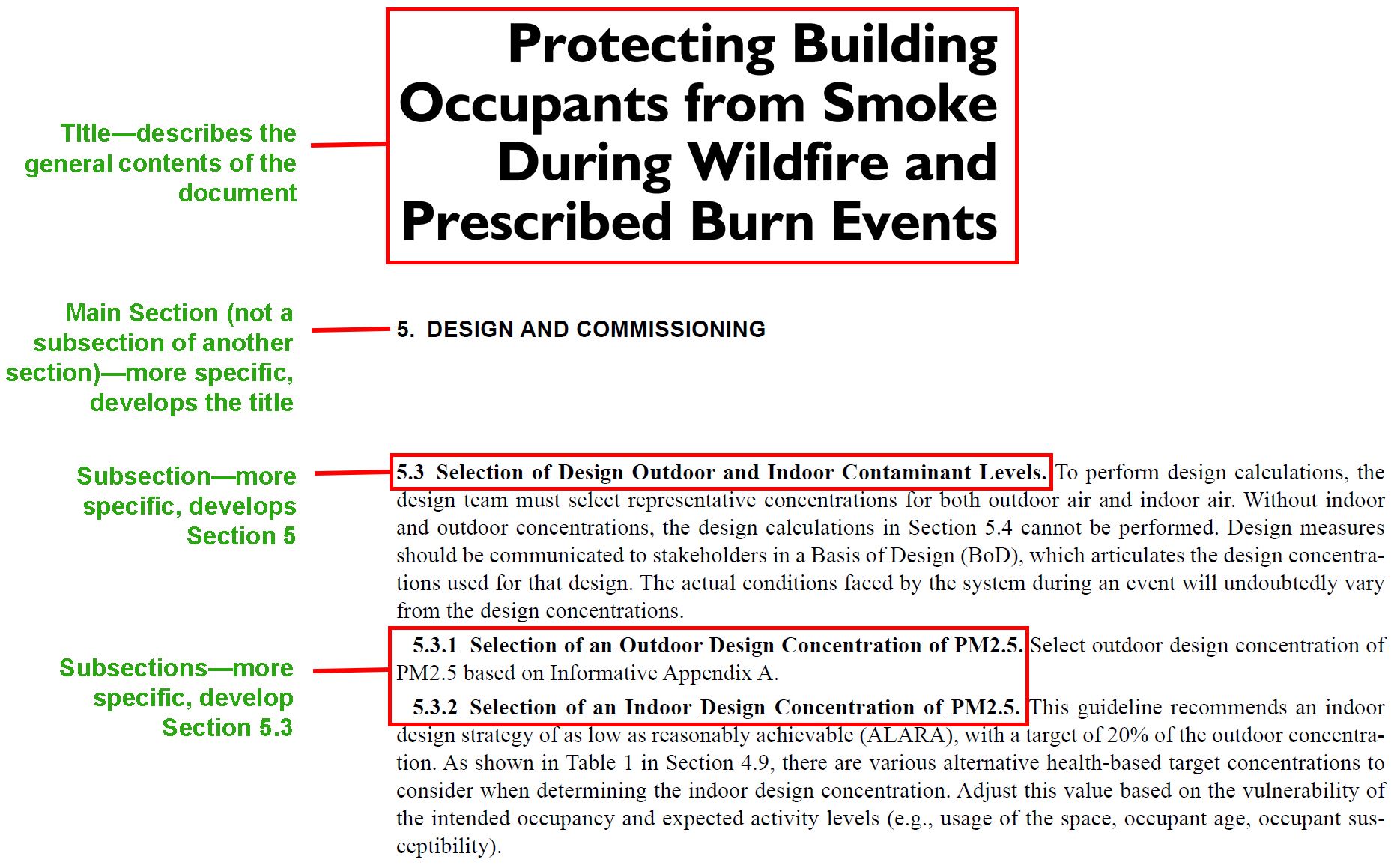

Organization is the orderly and intuitive arrangement of information from general to specific in a manner that’s accessible and easy to follow. The general direction of increasing specificity in the document is Title > Section > Subsection > Paragraph > Sentence.

Structure is the basic outline of a document. Each ASHRAE standard and guideline is composed of a main body and one or more appendices. The structure of the main body and each appendix follows the same basic pattern:

Title

Sections

|-----Subsections

|----------Paragraphs

|---- Sentences

Lists

Tables

Figures

Equations

Lists, tables, figures, and equations can appear in any section, subsection, or paragraph.

Titles

The document title is a concise description of the subject. Every part of a standard or guideline should relate to the title or be omitted.

An appendix title is a concise, general description of the subject of an appendix. Every part of an appendix should relate to the appendix title or be omitted.

Sections

Sections are the primary organizing unit of a document.

A section is a main section (e.g., Section 1, Section 2, etc.) if it isn’t a subsection. Main sections develop the title in greater specificity.

Subsections

The term “subsection” is a relative way of describing how a section is ordered in the document.

A subsection that has its own subsection(s) is also considered a section. For example, Section 5.3 is a subsection of Section 5, Section 5.3.1 is a subsection of Section 5.3, and so on. Subsections develop sections in greater specificity.

NOTE: Refer to all sections and subsections in the document as “Section x.x.x” and not “Subsection x.x.x.”

For more on subsections, see Choose the Right Tool.

Modular Design

Standards and guidelines aren’t designed to be read from cover to cover. The user’s path through the document is determined first by area of need or interest, then by the relationships between sections as indicated by cross reference.

A modular design reduces repetition and is easier to use, update, and maintain.

Paragraphs

Use paragraphs to organize information inside sections or subsections. Try to limit the number of ideas developed by a paragraph and use multiple paragraphs to develop multiple ideas. Paragraphs don’t need to relate to one another (though they can), but all paragraphs should relate to their common section or subsection.

See Choose the Right Tool for guidance on when to use a paragraph vs. when to use a section.

Sentences

Sentence structure is one of the most important elements of writing, and perhaps the most poorly understood. Sentences build out ideas. Each sentence in a document should incrementally advance the topic of a paragraph or subsection.

Most common composition mistakes are made at the sentence level. For tips on crafting better sentences, see Grammar and Word Choice.

Lists

Lists are primarily used to format several items in a series so they’re easier to read or easier to cross reference elsewhere in the text. Compare, for example, the same text in a single sentence versus in a list:

The specified HVAC system shall incorporate the following integral components: the condensing unit, responsible for heat rejection; the evaporator coil, facilitating heat absorption; the air handler and blower unit, circulating conditioned air throughout the system; the furnace, providing heat generation; the return and supply ductwork, conveying air to and from conditioned spaces; the refrigerant lines, transporting the working fluid; the air filter, removing airborne particulates; and the thermostat, enabling user control of temperature settings, all of which are essential for effective system operation.

versus

The specified HVAC system shall incorporate the following integral components:

- Condensing unit (responsible for heat rejection)

- Evaporator coil (facilitating heat absorption)

- Air handler and blower unit (circulating conditioned air throughout the system)

- Furnace (providing heat generation)

- Return and supply ductwork (conveying air to and from conditioned spaces)

- Refrigerant lines (transporting the working fluid)

- Air filter (removing airborne particulates)

- Thermostat (enabling user control of temperature settings)

A secondary use of lists is to provide an outline or sequence of instruction.

Avoid mixing complete sentences and sentence fragments in lists. Choose one or the other and be consistent.

Lists should never be used arbitrarily or as a last resort because the author isn’t sure how else to format the material. Results will invariably be poorly organized text that’s difficult to read.

For more information on using lists effectively, see Choose the Right Tool.

Tables

Tables are usually self-contained and have their own organizing structure comprising rows, columns, cells, and headers/footers. Organize information in tables with readability and usability in mind. Arrange information in a logical fashion and use descriptive labels to cue the reader on how to read the table. For more information on table requirements, see the Author Checklist.

Figures

Very detailed images with small text may be difficult for some users to read—especially in printed form. Because standards and guidelines are printed in black and white, charts and graphs that use color, particularly gradients, to convey information will be unreadable to print users. Wherever possible, create graphics that are easy to read across multiple media types. For more information on figure requirements, see the Author Checklist.

Equations

Consider numbering equations if you intend to cross reference them elsewhere in the document or your document includes a large number of equations. For more information on equation requirements, see the Author Checklist.

Cross References

A modular approach to organizing and writing can help authors maintain focus and avoid redundancy. Instead of repeating information from other sections, cross reference those sections. A cross reference is any part of the document that is mentioned by number somewhere else in the document. Sections, Tables, Figures, Equations, and Appendices should all be cross referenced (e.g., Section 9.3.2, Table 6-1, Figure 3, etc.).

Always be specific when referring the user to another part of the document. Never use vague directional language (e.g., “above,” “below,” “previously,” “later,” “before”).

PDFs and Cross References

Cross references to sections, figures, tables, equations, and appendices are converted by staff to clickable hyperlinks in the PDF version of most ASHRAE standards and guidelines, providing users a convenient means of navigating the document. Thoughtfully organizing your document and consistently labeling cross references explicitly in the document (e.g., “… can be found in Section 5.4”) will improve navigation for most users.

Return to Planning | Top of Page

Coordination

Writing assignments are typically divided among members of the committee. One author may be responsible for multiple sections, and one section may have multiple authors. To the reader, there is only one author of every standard and guideline: ASHRAE.

Creating one unified authoring voice from several is important to maintaining ASHRAE’s authority, credibility, and brand, and requires coordination by the committee.

Tips for Coordination

- Prior to writing assignments, define terms precisely as they’ll be used, and use terms precisely as they’re defined. If a thing has multiple commonly used names, pick one and use it everywhere.

- Prior to assignments, define a single list of abbreviations, initialisms, and acronyms for all authors to use consistently.

- Review ASHRAE requirements for dual units. Determine the order in which dual units will appear in all sections—I-P (SI) or SI (I-P).

- Provide a copy of the Author Checklist with each writing assignment.

- Prior to public review, assign one or more people to review and ensure that writing assignments conform to the requirements of the Author Checklist.

Return to Planning | Top of Page

Timelines

Some documents take longer to write than others due to the complexity and scope of a topic and the necessity of building consensus, or due to outside factors that limit the committee from moving forward in a timely manner.

Projects that enter the writing stage and then stall for too long risk becoming outdated due to advances in technology and other industry changes. Once lost, momentum is difficult to recover and document cohesion may suffer.

Tips for Navigating Timelines

- Be fully aware of the ANSI procedures for standards development in order to avoid procedural delays. Direct questions to the SPLS or staff liaison.

- Make writing assignments; set reasonable, regular deadlines, and try to meet them.

- Avoid making any project too dependent on only one or two people.

- If a writing assignment stalls for whatever reason, ask the author to complete the Author Checklist to the extent possible as a way of documenting what remains to be done.

- Back up Author Checklists to a central location (e.g., an ASHRAE OneHub workspace) for future reference.

Return to Planning | Top of Page

WRITING

GRAMMAR AND WORD CHOICE | WRITE TO ORGANIZE | WRITE EFFICIENTLY

Write simply. Writing choices shouldn’t make complex topics more difficult to understand. Simple writing is clear and efficient. It foregrounds concepts and ideas and makes them accessible to the reader. It doesn’t distract from what’s being communicated.

Grammar and Word Choice

At the sentence and paragraph levels, the words you choose and the order in which you arrange them are the most important factors in clear, concise writing.

Write Complete Sentences

Every sentence must—at minimum—include a subject (actor) and verb (action). A sentence that lacks a subject and a verb is a sentence fragment. The ASHRAE staff editor will always ask that sentence fragments be rewritten.

Active vs. Passive Voice (Arrange the Actors)

Think of each sentence as a very short play where one actor (the subject) performs an action (the verb), and another actor, prop, or setting (the object) receives the action.

The team (S) implemented (V) the solution (O).

This order of action (Subject -> Verb -> Object) is called active voice. Active voice generally results in clearer, more concise, more readable sentences. Compare the example above to the same sentence using passive voice:

The solution was implemented by the team.

The first sentence is shorter and also easier to understand based on the order in which the average person expects to receive information.

Passive voice may be preferable in some cases. When in doubt, err on the side of readability.

Read more on active and passive voice here.

Verb Usage (Manage the Action)

In sentences, verbs provide the action. All verbs share two characteristics important to technical writing:

- Tense indicates whether the action occurs in the past, present, or future.

- Aspect indicates the flow of time for an action: whether it’s completed, continuous, both, or neither.

In your writing, the action can change quickly, for example, from describing how a process works to proposing future action that will need to be taken as a result of following a process. This means the tense and aspect of your verbs will also change.

Changing tense and/or aspect too often, or mixing them incorrectly, can lead to confusing timelines and ungrammatical sentences, which can make a document more difficult to use.

When in doubt, try rearranging the sentence for clarity, breaking longer sentences into smaller ones, switching to active voice, or otherwise rewording for clarity.

Read more on tense and aspect here.

Unclear Pronouns

Pronouns are—by far—the most common source of unclear, unreadable text. To avoid unclear pronouns:

Examples of Unclear Pronoun Use

Vague or Ambiguous Reference

- Original: The new software module was deployed, and it significantly improved system performance.

- Problem: "It" could refer to the software module or the deployment itself.

- Revision: The new software module was deployed, resulting in significantly improved system performance.

Unnecessary Subject

- Original: It is important to note that the sensor must be calibrated before use.

- Problem: Starting sentences with "It is" can be wordy and distract the reader from the main point of the sentence.

- Revision: The sensor must be calibrated before use.

Excessive Use in a Single Sentence or Paragraph

- Original: The system has a self-diagnosis feature. It detects malfunctions and it then provides troubleshooting steps. It also generates reports on its findings.

- Problem: Repetitive use of "it" makes the sentences feel clunky and less professional.

- Revision: The system has a self-diagnosis feature that detects malfunctions and provides troubleshooting steps. This feature also generates reports on its findings.

Passive Voice

- Original: It was decided that the project would be delayed.

- Problem: Using "it was decided" can lead to passive voice, obscuring who made the decision and making the writing less direct.

- Revision: The team decided to delay the project.

Avoid Terse Writing (Shorthand)

Terse writing omits critical information and assumes the reader has specialized knowledge to understand anyway. Terse writing is often mistaken for efficient writing.

Terse writing often takes the form of shorthand, a short, informal way of expressing something.

For example, the phrase “meets operation” is shorthand for “meets requirements for operation.” The author may understand the two phrases to mean the same thing but shouldn’t assume the reader will.

Shorthand is inappropriate in ASHRAE publications unless formally defined in the document before it’s used.

Choose Simple Common Words

Don’t choose common words based on how technical or official they sound.

For example, many authors use utilize/use and enjoin/join interchangeably, but the words in each pair mean different things.

Unnecessary complexity doesn’t make writing appear more authoritative, only more difficult to read. As a general rule, given a choice of common words, choose the shorter one. If you’re unsure of the meaning of a word, consult an online dictionary.

Avoid Idioms, Cliches, and Jokes

Put simply, these are inappropriate to technical documents and should not be used.

Return to Writing | Top of Page

Write to Organize

Some sentences and paragraphs signal certain things to the reader based on where they appear and can be used to guide reading. Use sentences and paragraphs to declare intentions and summarize ideas.

Keep It Modular

Think of sentences in a paragraph as parts in a model airplane kit. Each sentence describes part of the airplane, and if you assemble the parts in the correct order, together they describe something easily recognizable as an airplane.

However, if you assemble the parts in the wrong order, the thing you describe might not resemble an airplane at all, or worse, it might resemble a (very poorly designed) train.

Before you write, and as you write, think about the order of the parts. Where some parts (topics or ideas) are too large to assemble, break them into smaller parts that fit together more intuitively.

Think of paragraphs in a similar way. Just as sentences are combined in an optimal order to create paragraphs that express clear ideas, so paragraphs are combined to create sections and subsections.

Pants First, then Shoes

A common mistake is to introduce Concept A when discussing Concept B before first explaining what Concept A is (or how it works).

Be aware of the order in which you introduce information, and provide proper context for the reader.

Label Information

Subsections in most cases should include a section heading that summarizes their contents. Headings are invaluable, as they cue the reader on what’s coming, which makes the reader more receptive to the content.

Paragraphs don’t have headings, but the first sentence or sentences of a complex paragraph can be used to assert what the paragraph is about and/or what it intends to do.

Tables and figures should always include titles and captions, respectively.

Summarize Strategically

When developing complex, interrelated ideas, look for natural transitions points where it’s appropriate to summarize in one to a few sentences what’s come before as a way of refreshing the reader before continuing. Short summaries will create a conceptual bridge between related topics or ideas and aid comprehension.

Exercise discretion, as oversummarizing or summarizing too often can be distracting for the reader.

Return to Writing | Top of Page

Write Efficiently

Don’t Overexplain

You may need several tries to clearly articulate an idea. Perhaps the first attempt doesn’t fully capture a concept or is worded in a way that may be incomplete or confusing. When this happens, don’t try restating the same idea multiple times in different words. Stop and edit what you wrote to more clearly express the idea the first time.

Phrases such as “In other words,” “To put it another way,” and similar should be a sign to stop and revise rather than continue.

Use Shorter Sentences

Many incoherent sentences can be resolved by breaking them into two or more smaller sentences. In general, short-to-moderate length sentences are less likely to be ungrammatical. They’re less likely to have unclear pronouns or suffer from confused tenses.

There’s no ideal sentence length, and longer sentences may be more appropriate in some circumstances. Ultimately, the measure of whether a sentence works is if it makes sense.

Avoid Unnecessary Transition Words/Phrases

Well-organized sentences build out ideas in a formal, systematic way, and the transitions between them are implied. Too many transitional words or phrases, such as “thus,” “therefore,” “it follows,” etc. may indicate unclear organization or writing and that revision is required.

Return to Writing | Top of Page

PROCESS

STAY FOCUSED | CHOOSE THE RIGHT TOOL | CHECKLISTS | REUSING MATERIAL

Stay Focused

Length

The lifespan of many standards and guidelines can be decades, and documents have a tendency to grow longer, never shorter. Committees should think critically and strategically about every new addition to a document or risk content creep.

- Longer documents aren’t necessarily more impactful, and a document’s importance isn’t determined by its length.

- Length can negatively impact usability. Longer documents are more difficult to review and revise and susceptible to lapses in quality control. Authors working on different sections may duplicate information or even produce different, conflicting versions of the same information.

Scope

Content, including all informative text, should not exceed the stated scope of the document.

Historical Information

Historical information is almost always out of scope in a standard or guideline and should be limited to the foreword.

Subject

Avoid duplicating material found in other standards and guidelines. Wherever possible, reference existing documents instead.

Example: Commissioning

Commissioning is a common subtopic of many ASHRAE standards, and ASHRAE publishes a small library of standards and guidelines related to building commissioning. Where possible, reference these existing documents rather than reproducing the work of other committees.

For example, Standard 90.1 specifies a small, high-level subset of commissioning requirements for various building systems but references Standard 202 and Guideline 0 for a full set of requirements. The commissioning material unique to standard 90.1 is less than two pages, much of which is self-referencing.

Appendices

Appendices can overwhelm a document, in some cases doubling or more its length. Consider the following when evaluating whether to add a new appendix:

- Appendices shouldn’t be used as an ad-hoc user’s manual.

- Appendices are not a clearinghouse for topics of marginal relevance.

- Appendices should benefit a large majority of intended users.

Appendices vs. Supplemental Files

Some material is unsuitable to appendices and better included as downloadable supplemental files:

- Samples

- Examples

- Forms and templates

- Case studies

Supplemental files are provided to users as-is and are accessible via a persistent URL in both print and PDF versions of a standard or guideline (a clickable hyperlink in PDFs).

Don’t format these materials as appendices. Instead, submit them as separate, individual files (Word, Excel, PDF, etc.) to be included for public review.

Supplemental files can’t include normative material.

Other Publishing Options

Standards and guidelines aren’t the only publishing opportunity available to committees. Some content may be more appropriate to one of the following:

- A white paper

- An article or podcast

- An ASHRAE education course or online training

Contact the Editor of Standards and Guidelines to explore potential options.

Return to Process | Top of Page

Choose the Right Tool

Key to clear writing is understanding how to organize content to be most accessible and impactful. The following sections discuss common choices authors face and how to approach each.

Paragraph or Subsection?

At a basic level, subsections are just numbered paragraphs. There are no firm rules for when to use a subsection and when to use a paragraph. Generally speaking, a balanced mix is desirable.

Subsections are most appropriate when a specific paragraph (i.e., concept, idea, or requirement) needs to be cross referenced elsewhere in the document, or when key ideas need to be more clearly separated and labeled.

Consider usability. Don’t automatically format all paragraphs as subsections without good reason; instead, use subsections to organize key ideas and avoid large amounts of lightly formatted text.

List or Subsections?

Lists pose a trap for authors short on time. Numbered lists provide the same basic organizational utility as numbered subsections but the two aren’t interchangeable.

Lists are a way to group related items for reference in a section or subsection; they’re most effective when short and accessible.

Lists shouldn’t be densely packed with information. Formatting lists as long paragraphs defeats the purpose of a list.

Lists are appropriate in cases where list items are short: a word, a brief phrase, or one or two sentences at most. A section/subsection structure may be more suitable to longer, more complex but related items.

If your list is a collection of lettered or bulleted paragraphs, consider restructuring it using numbered subsections with headings.

Always avoid formatting simple lists as numbered subsections.

List or Table?

In most cases, a simple list shouldn’t be formatted as a table unless the author intends to cross reference the full list by number elsewhere in the document.

Unbalanced Lists

A dense list can be rewritten by moving extra explanatory information to paragraphs before or after the list, or, in cases of extreme density, restructuring the list as a series of sections and/or subsections.

The order in which list items are discussed should mirror the order in which they’re listed.

Don’t be afraid to separate list items and explanatory text. This is a common and intuitive way of organizing information, and it will make your document easier to read and understand.

Return to Process | Top of Page

Checklists

Use checklists to help organize work and verify completion of required tasks. Checklists will help ensure a smooth path from development to publication. ASHRAE provides the following checklists to authors and encourages their use:

Author Checklist

Author Checklist

Writing Good Definitions

Writing Good Definitions

Return to Process | Top of Page

Reusing Material

When repurposing material, be aware of the rules governing copyright.

Material Authored by the Committee

Committees are permitted to include or adapt material previously authored by their members, provided no other organization asserts copyright over that material (see Non-ASHRAE Material).

Other ASHRAE Material

Except for very short excerpts, authors are strongly discouraged from reusing material from other ASHRAE publications. In most cases, authors should simply reference other ASHRAE documents by title and/or other designation (e.g., standard number). E-mail requests for exceptions to the Editor of Standards.

Non-ASHRAE Material

Reuse of materials copyrighted by organizations other than ASHRAE requires written permission by the owner. Permission must be submitted with the publication draft prior to publication.

Return to Process | Top of Page

REVIEW

REVISING AND EDITING | QUALITY CONTROL | POLISHED APPENDICES

Revising and Editing

At the end of the process, fatigue sets in, and the finish line is tantalizingly close. At this point, resist temptation to skip or skimp on document review. The revising and editing process is what makes good documents great documents.

Editing and revising is the best opportunity to apply the guidance in this tutorial:

Return to Review | Top of Page

Quality Control

Use the Author Checklist and a coordinated revising and editing plan to help ensure quality control.

Because documents can sometimes take years to write, and much changes from draft to draft, take time to review all callouts to numbered sections, figures, tables, and equations—including those from other publications cross referenced in the document—to ensure they’re current and correct.

Failure to account for changes in numbering from one edition to the next can introduce serious errors.

Return to Review | Top of Page

Polished Appendices

Give appendices the same scrutiny and polish as the rest of your document. If you repurpose material from another source, remove cross references from the original source that no longer apply, and update the content to match the organization and style of the current document.

Return to Review | Top of Page

September 4 2025